- Home

- Ron Charach

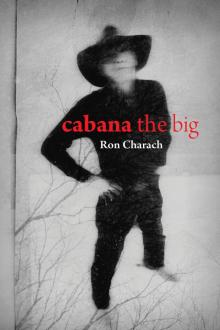

Cabana the Big Page 2

Cabana the Big Read online

Page 2

About the only time she lectures—ma does—is when one of them’s been wounded fer real—most often by cabana since he never-ever loses. She’ll cry as she holds a com-press to a slashed arm or leg or a split upper lip.

—O for sem a’ ma’s cider, grits big ned somewhere, wipin’ the sweat off his brow with a crusty ole forearm. His pointy teeth take on a smile as he considers ma rosemary smilin’ back at him even though she’s a good five miles away. The only other livin’ thing that’ll smile back at ned is cabana who does it frequently on a dare. Course, dust-covered rattlers on the range will show him two drippin’ fangs apiece and one day will get him—if cabana don’t first.

Maybe one’ll surprise him this very night as he struggles with those range-beans with the sand mixed in ’em that crunches like glass, an’ farts up a Mel Brooks sandstorm gettin’ flashbacks of fresh bread and cider—and ma, da good ole painted lady ’at makes ’em.

louise

Louise lies belly-down on the last bit of lawn left anywhere, runnin’ her slender fingers through the lost memory, whimperin’. She strains and pulls up little handfuls thrown high into the air as she laughs and catches her breath then looks around, then does it right over again without even wonderin’ why. Post-apocalyptically.

She walks back home while the dim light still shines, sad whenever she looks into the lemony orange sky, brushin’ wisps of hair fallin’ over her watery eyes. All she wants is to have someone who understands and who cares. What girl of fifteen could do otherwise?

Her sweater around her waist in a bow that she ties and unties, lyin’ still in the shadowy sundown of the small deserted farmhouse where she lives almost alone—out of view of the dull glass dome in the distance from which only fearsome riders would venture. And she looks up from the middle o’ nowhere—like the girl in Christina’s World.

jamie

But all is not innocent or still. Louise has a little boy and he belongs to her. The story of how it was—when Louise was grabbed and pushed apart and hurt while she fell into a merciful swoon—is too much a nightmare to recall. Just to say that she had carried a little boy inside her and brought him out with the help of a mercy visit from a handsome mid-life midwife known only as ma.

She nurses him with still-pointy breasts and she washes him.

She guards her little one—readin’ him stories of a happier time as he dozes in sleep natural as a seagull on a dump-site—before leavin’ for the silence of the wild lawns of astro-turf outback. Always sure to return before he awakens—to a mornin’ song, a warm hug and honey kiss.

She lives with her candy boy. And no one knows but ma rosemary and a CEO on a horse who brings what they need every now and then—no one else feels these sad peaceful days of lazy rollin’ on the last remainin’ bit of furry green; no one else knows of Jamie’s frolickin’ in cotton dreams, the two of them in cradles rocked by sickly listin’ westerly winds.

Powers That Be

time slots—cabana’s vow

This mornin’ cabana’s patrollin’ the streets at 6:45 a.m., for a reason that can be best summed up in one simple word: Friday.

It’s like this: first thing in the mornin’ is prime moseyin’ time. Not a soul in town is up except for ma rosemary and Carla, who have to prepare for their daily services during the wee hours. Or maybe galloway’s off somewhere, dozin’ by one of his closed-circuit monitors.

Now you might guesstimate that any of the big ones energetic enough to be up at 7:00 a.m. after a wild night of drinkin’ and gamblin’ would have free reign to stop in for a cider or a health check at ma’s or a few pints and an eyeful at Carla’s. But there’d be a catch to any one of ’em takin’ advantage of so sought-after a privilege: each of ’em is after it. And no two of ’em can walk a street at the same time without takin’ at least one or two potshots at t’other. The temptation of two hung-over, ornery men walkin’ a deserted street in the middle of a desert town would make for showdowns a priori—if not sooner.

So the big ones—and there are eight prowlin’ these parts—must rely on the help of galloway’s mock-Crackberry to divvy up the early-mornin’ shifts—not for love of order or schedules but as a measure o’ pure survival.

On Mondays fallin’ on even dates cabana patrols the old main street and heads on up to Carla’s or ma’s. On Mondays-odd, it’s the turn of no one other than fat-ass jake—strictly WWF material. (World Wrasslin’ Federation not World Wildlife Fund—ya enviro-dweeb!) Tuesdays are shared by billy, even, and bloody willy, odd; bloody willy has an arrangement that if he can’t make it he’s stood in for by his younger brother bloody willy too, whom nobody’s ever met. Wednesdays go to big ned—alternatin’ with a cousin of the big eight, a late in-duck-tee, the former medic henry morgan. While on Thursdays it’s the trapper dan show. trapper gets Thursdays odd and even ’cause he’s too loco to figure out the difference. In fack there’s been talk lately about re-vokin’ his early mohnin’ privileges, on accoun’ o’ he squanders the morn without botherin’ to visit Carla or ma. He fritters away his prime time settin’ grizzly bear traps all over Main Street that a specially ass-igned townsman named Parkinson has to spend half of Thursday afternoons removin’.

It’s worth ten seconds (no more) to explain the unique personality of trapper dan, t’do a genetic-dynamic formulation of this redoubtable gent. trapper is constantly approachin’ folks and darin’ ’em to bean him on the head—claimin’ not without jestification that his head is a mite-shade harder than granite. His personality is testimony to just how many people have taken up the invite. Even a classy dude like cabana took the time to bop that old eggshell of trapper’s with a meat tenderizin’ mallet offered expressly for that purpose.

So even though it don’t make sense to let trapper dan stalk imaginary grizzlies while the rest of the big ones hanker after bare-naked ladies—he hangs on to Thursdays odd and even and will go on keepin’ them ’til cabana or henry morgan or a notice from galloway at head office decides it’s worth the time and effort to exterminate that brain-dead varmint.

Fridays-odd go to slick black amos barton—also new to the big set—the silver-spurred dandy of the group—gated comm-unities and racial profilin’ be damned. He’s the last-but-not-back-seated number eight of the big ones.

Well that might cover the handlin’ of the mornin’ times—’cept once they were divvied up there were still times left over. Namely: Fridays-even, Saturdays-odd and even and Sundays-odd and even.

Sundays-odd and even went out o’ commission suddenly when Carla took to decidin’ to sleep in late that day—fer her beauty ’n all. Saturday nights bein’ particularly hectic and requirin’ ample recovery time. Fridays-even were snatched up neatly in a coup by cabana amid an uproar that lasted five suspense-filled seconds—’til cab reached down for his ’gator belt with the ammo clips. Saturday-odd fell to big ned, which left only Saturdays-even. Fer a change of pace Saturdays-even were awarded to cabana.

Worth notin’ that should big ned ever con-fuse an odd with an even he’d meet square-on with cabana on the latter’s day. Which is why ned’s backside (shaved slick for the purpose) is tattooed with a calendar—December through May, June and Ju-ly on each hammy buttock and August through November runnin’ down the back o’ each leg. Carla sometimes calls him My Calendar Boy—though The Illustrated Man ’d be more like it.

With all that explained it’s not too difficult picturin’ cabana sidlin’ kind o’ vertically up the old main street on a sun-fried Friday with not a soul astir in the entire town ’ceptin’ Carla who happens t’be the proprietary pie of the very place where he is headin’.

With steely deliberation he moves his left leg then his right, hinges creakin’ slowly, coolly, pins in his shoulders makin’ faint warnin’ noises—like a saloon sign slappin’ in a dust storm—that give others plenny o’ time to va-moose. The pins stem from an ole gunfight with big ned durin’ which cabana had b

oth arms blown clear off—only to have them affixed right back on with a couple o’ ma’s trusty bobby pins. To this day, any time cabana sus-stains a flesh wound there, you can spot tiny flecks o’ dandruff that once nestled in that good little woman’s hair lyin’ scattered along ditches o’ dermis.

cabana, lookin’ askance, half-expects to get a flash of ned down the way though there’s nothin’ but sagebrush blowin’ down Main Street and no sign o’ townsfolk save a broken-down wagon some poor dude had t’leave behind once he realized what day it was and checked the fine print o’ his life insurance for a clause that might limit the amount payable.

Straight before cabana’s geodesic gaze appears this flashy new sign—a sign with a difference—an ad-dendum:

CARLA’S SALOON—Take Yore Spurs Off*

*big eight Ex-clooded

With a little smile kind o’ inchin’ up on him, cabana gives his buckskins a brush, secretes the smallest amount of WD-40 on his forehead for some shine, squeezes his vice-grip hands—an’ mounts the steps to that curvaceous cutie. Pushes open the wooden saloon doors bitquicker t’avoid them swingin’ straight back on him—goddamn them doors—and is bathed in the soft light o’ a buck-antler-cum-crystal chandelier hangin’ over tabletops of buffed cherry wood. As Carla primes the beer taps, her nervous helper Lucy frets away at the back, sneakin’ a toke of aromatic freeze-dried BC bud, courtesy of harold galloway.

Now if’n he were jest any young cowpoke he’d a’ simply parked a Hummer with antelope-catcher, hauled out his cell phone and while on a call simply said Mohnin’ to Carla and her young dys-morph assistant. Maybe order a pint while fiddlin’ with his portfolio on a hand-held devious, maybe an I-me-me-my-Phone or a And-droid or a nostalgic Canuck Crackberry—and only after he is good an’ finished, exchange a few words with the comely young lady or text-massage her, sext her or jest send her a poke or a tweet.

But cabana says sweet diddly. Jest cringes his inner lips—tight enough so you’d need a pair o’ Bushnells or an Owl restaurant light to spot the motion. From the outside he looks like he was hacked out o’ stone with a chisel or like some huge slab o’ con-glomerate careened off the side of a rockface. Calm and craggy: he blows dust off his sleeve onto the bar an’ tightens his widely rangin’ arm t’reveal flexors an’ extensors of Schwarzenegger variety—then grips a beer glass that Carla slides his way nice an’ smooth-like. Aimin’ for the ashtray, he spits into it a thin sliver of metal. Then in-spects Carla as she sits there lookin’ near as wily as wary. And all this time naughts the word. Just sittin’ there sippin’ alcohol—incorporatin’ it into his limbic centers with the efficiency of Japanese blottin’ paper.

Lucy knows better than to look up—never while cabana is savorin’ a silence. After fifteen minutes of such, Carla dares to stretch her curvy back along the wall of pioneer log, and up through her ribless waist of pure sinew and frisky-puppies chest she eases a whisper: —Ain’t ya heard, cab?

Nothin’. Not a movement. Not a flicker of ak-ak-ack-knowledgment. Carla waits—her slender foot tremblin’ just a tad below the bar rail as cabana takes to strokin’ the longer edge of his beer glass.

Little Lucy petrified. Watchin’ clouds in her coffee. Sees cabana all stony and unflinchin’ and recalls how he once stood jest the way he’s standin’ now: then in a second a furnace flash as he hauled out his silverware and pumped twenty bullets into a townie who’d asked in the wrong way: —Excuse me, sir, but is this seat taken? Evidently, tragic’lly, it was.

But a tiny crease starts across his face, two creases, movin’ downward into definitive lines. Lucy drippin’ sweat, tryin’ her best not t’look up. Wants to scream HELP! when the cringe turns into a pointed grin. An’ cabana slowly answers

with a slow turnin’ of his turret—in a kind of a no.

Once cabana lets you live you might as well keep talkin’—havin’ by-passed the point of maximum danger, though Lucy’s bite-plate is saggin’ as her boss forges on: —galloway…

No change in cabana’s flintlocked face.

—galloway’s done terminated my lease; wants to turn the saloon into—an’ she mimics the runt who sounds out his every word, proper as a Muskoka-cottage Canadian—a “profit-making ventyoor.”

More silence.

She goes on: —So I says to him, hell with you, ya Ivy-League-intellectual, Wall-Street-apologizin’ loser. I ain’ goin’ to up my prices none—even if you do so happen t’provide the nourishment an’ call y’self mah uncle. I bin handlin’ service ’round here two long years now an’ I see the big eight ’at stop by here as my boys, same way’s ma rosemary.

cabana may have nodded his head a mite at the mention o’ ma.

—An’ he answers back, galloway does: —Please refrain from comparing yourself to ma. It’s dis-respectful. Just like that, he answers me. So I tells him—uncle harold—er, galloway: —You keep yore stinkin’ money.

—But he won’t take no fer an ans’er. He says —If you don’t co-operate, I shall have to revoke your license or perhaps travel to the nearest neighboring “town” where there just might be a C-for-Certified Marshall, posse in tow, or remnants o’ the National Guard to make sure that the eight and their little server-girl go the way of all other flesh. And wouldn’t I like to save him from goin’ to that kind of trouble—knowin’ full well that he’s docketin’ his time like a partner-track corp’rate litigat’r even as we speak?

No movement from cabana. Carla pressin’ a dishtowel to her décolletage.

—So finally I says to him: —Jest what do you think cabana might say if’n he knew that some fed’ral marsh-all and his pissy little posse or a dozen neo-Nazi guards might be payin’ us a visit? To which he answers—and I kid you not: —cabana, shmabana—

cabana veers. A twelve-ton cat swervin’ like an Abrams as Lucy faints—nose dippin’ into her coffee and bubblin’ like a small toy boat goin’ down in a bathtub full o’ Soaky. Flips a piece o’ silver out o’ his pocket, throws it clear over his shoulder so’s it lands smack-dab in the center of an ashtray—and he’s outta there—legs bowed with rhino intent, with the word galloway breakin’ out in veins across his temples and his sculpted lips a bloodless white.

big ned is summoned

Two hours later that same Friday big ned wakes up. The early awakenin’ may be without precedent, but it is not without cause. For big ned had been dreamin’ about a little insect takin’ a walk along the inside of his skull, makin’ tiny stompin’ noises as it wriggled ’round his hemi-spheres with imp-yoonity—bleatin’ indistinguishable insect gibberish as it scratched along his semi-circular canals. This enraged big ned since any intruder into his lair was likely smart as he was, the cave dust notwithstandin’.

His eyes open wide. He can tell they are open ’cause suddenly he can see—all-be-it filmy at first. Things generally look fa-miliar: The splash o’ puke on the mattress from last night’s bender, the urine stains—goddamn that asparagus!—the red mud on the doormat—the sour remains o’ milk spilt from the cracked bowl on the yellow washstand. Even the straw tickin’ on the cave floor jest lies there—spider webs full o’ abandoned li’l legs—like a tab-low straight out o’ Better Caves and Gardens.

Except for that confounded natterin’. Instead of the muffled noise of the man-made waterfall gushin’ outside the boulder door, ya have these crazy li’l insect steps.

big ned cusses himself for startin’ dreams he cain’t finish. Tells the insect to bugger off and is about to stuff his head into the thickest of the spiderwebs—sort o’ try to off-load that insect to one of those chubby but merciful-quiet spiders—when suddenly the noises draw together, into a distinct: —big ned big ned, please, are you in there!?

—Goddam’ insec’ a-hole—up’n callin’ me lak thet! ned spits stringily—the nerve of an in-vertebrate actually callin’ his name. Why, dem insec’s so dumb dey can’ even wrat dey own names.

Volcanically: —Dis insec’ll take special gettin’ rid of! And pullin’ a torch off the cave wall sconce he is about to smoke the insect out o’ his head when he hears a slightly more distinct —It’s me—harold galloway!

—Dunno any bug ba thet name—’cept fer one.

ned shoves aside the boulder at the mouth of his cave to reveal galloway tip-tip-tappin’ at one of the cave walls with slender white signet-ringed fingers. galloway backs up at the sight of ned standin’ there naked as noon and then freezes. The insect noises cease. After lookin’ him up and down and debatin’ whether or not to crush him—ned settles for sweepin’ the air with his huge paw in a kind of Entrée-Euro-weenie gesture. After all, hadn’t galloway set him up in this plush little cave suite in the first place? big ned does a belly-flop on his mattress all damp with moanin’—mutterin’ obscenities into a lake of drool slowly eatin’ its way thru the pillow.

Cabana the Big

Cabana the Big